sculptor | mixed media

STEPHEN FREEDMAN

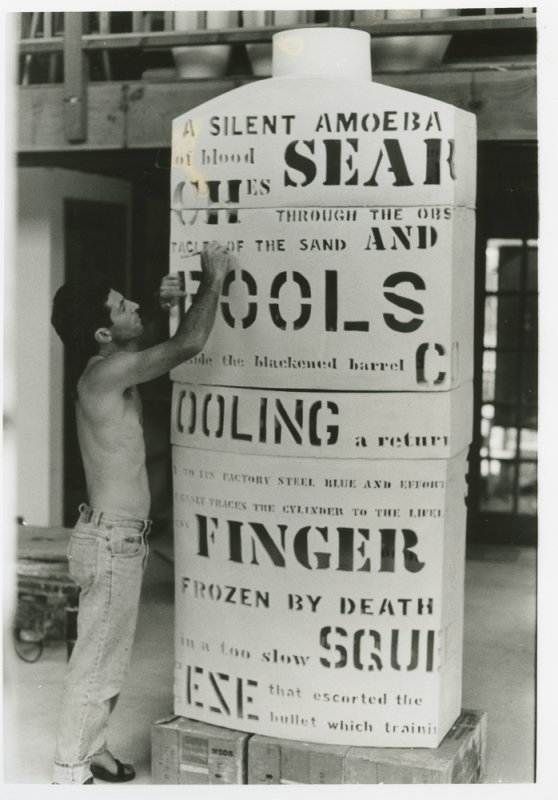

Stephen Freedman is a renowned sculptor and ceramic artist whose work reflects a lifelong journey of cultural exploration, resilience, and connection to nature. Born in South Africa into a family with deep artistic and scientific roots, Stephen was introduced to clay by his mother, a ceramicist. His upbringing amidst the rich natural landscapes of Africa and later Australia instilled in him a profound respect for the natural world, which continues to inspire his art.

Stephen’s career spans decades and continents, from digging clay in remote Australian forests to crafting large-scale sculptures in Los Angeles and Hawaii. His early experiences working with clay in isolation taught him to distill form into its purest expressions, often inspired by organic shapes like eggs—a symbol of life and renewal.

In Hawaii, Stephen’s work evolved as he embraced the islands’ natural beauty and cultural richness. His sculptures, informed by his background in evolutionary biology and storytelling, capture the intricate balance between humanity and nature. Each piece is a meditation on form, texture, and spirit, reflecting his journey through life’s challenges and transformations.

For Hawaii’s commercial clients, Stephen’s art offers more than aesthetic value—it tells a story. His large-scale installations and bespoke creations enhance spaces with a sense of place and purpose, bringing sophistication and meaning to any setting. With works exhibited internationally and a profound connection to his medium, Stephen Freedman continues to shape art that speaks to the heart of Hawaii and beyond.

Key Clients and Commissions Include

Ala Moana Shopping Center, ANA Hotel Tokyo, Chicago Hilton & Towers, First Hawaiian Bank, Four Seasons Resort Hawaii, Grand Hyatt Hong Kong, Mauna Lani Hotel, Sak’s Fifth Avenue, Shanghai Hilton, Westin Kauai